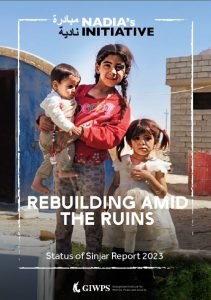

Rebuilding

amid

the

ruins

Status of Sinjar

Report 2023

Nadia explains the challenges ahead

The year 2014 marked the beginning of a long struggle for the Yazidi ethno-religious minority in Iraq

At that time, the non-state actors known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) began their campaign of genocide, which resulted in mass deaths, destruction, abductions, displacement, sexualized violence, and trauma.

Sinjar, the homeland of the Yazidis, was devastated by the occupation of ISIS and is yet to recover. Although liberated in 2017, Sinjar has lacked the development support necessary to facilitate a widescale return of the population.

Many Yazidis remain displaced to camps in other regions of Iraq, hesitant to return in the current circumstances.

Without the full restoration of basic services such as healthcare and education, or rebuilding of Sinjar’s devastated infrastructure and destroyed residences, much of the Yazidi population cannot return home.

Despite the challenges, thousands of Yazidis have returned to Sinjar with the hope that the region will recover. However, resources in Sinjar are limited, and reliance on aid programs leaves its future unpredictable.

Comprehensive efforts to sustainably redevelop Sinjar are required to support Yazidis currently living there and to allow for the widescale return of those who remain displaced

8 aid sectors and needs were assessed with clear findings and recommendations

Shelter

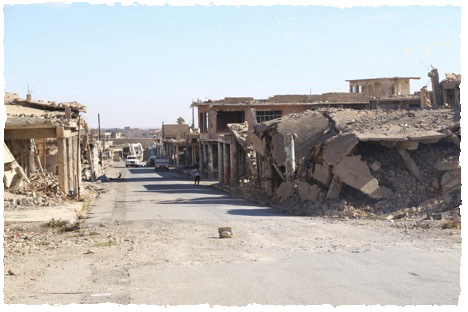

By 2017, when ISIS had been militarily defeated and Sinjar liberated, up to 70% of civilian homes in and around Sinjar City and 80% of public infrastructure throughout the region had been destroyed. Residents of Sinjar cite a variety of needs for re-establishing sustainable resettlement, including cash support, building materials, and legal documentation to assert claims to their original homes. The present challenges to housing leave Yazidis at risk of continued displacement within their homeland, marking an unpredictable future for many.

Findings

62% of Yazidi residents of north Sinjar are optimistic that they will eventually transition back to their pre-genocide residences versus 24% of those in south Sinjar.

35% of Yazidis currently in Sinjar remain displaced from their pre-genocide homes. Approximately 70% of surveyed men have been able to reclaim original residences versus 58% of surveyed women.

80% of Yazidi residents in north Sinjar cite affordability of building materials as the main limitation to transitioning to a permanent home. 55% of Yazidi residents of south Sinjar cite availability of building materials as the main limitation to transitioning to a permanent home.

Recommendations

- Increase efforts to rehabilitate residential structures for long-term and permanent use.

- Prioritize housing access for female-headed households.

- Prioritize efforts to rebuild homes in the south given higher levels of devastation.

- Prioritize provision of building materials to reconstruct homes across Sinjar.

Infrastructure

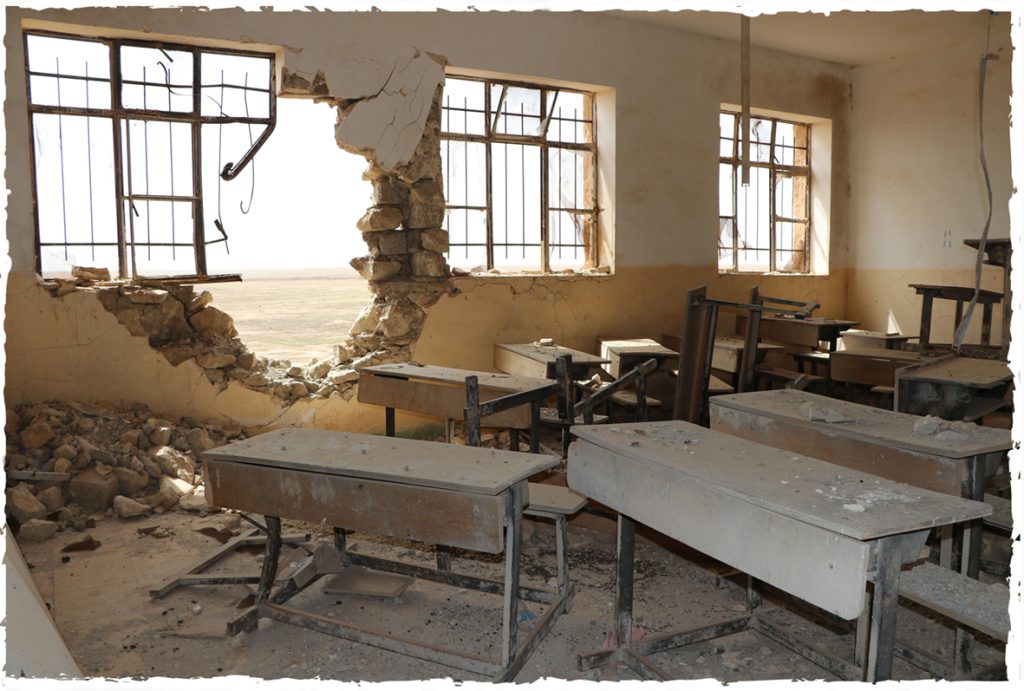

When ISIS destroyed essential infrastructure in Sinjar, they caused considerable damage to roads, electrical sites, health facilities, schools, and other public services. Sinjar requires extensive support to these sectors, especially to strengthen the current power grid and increase the availability of fuel. The unreliable electrical grid limits the capacities of health facilities and schools, and fuel is particularly important in the winter months when temperatures can drop below freezing and residential structures lack sufficient insulation from the cold.

Findings

All respondents in north Sinjar and 80% of respondents in the south have access to electricity for an average of 2 to 5 hours per day. The remaining 20% of respondents in the south have slightly higher levels of access at about 6 to 10 hours per day

90% of Yazidis in the north and slightly more than 50% in the south have limited availability of fuel (gas for vehicles, home heaters, generators, and other appliances). Where fuel is available, it is affordable to only 4% of respondents in the north and approximately 30% of respondents in the south.

Roads across Sinjar are in poor condition, non-existent and/or unpaved. This hinders development across most other sectors.

Recommendations

- Invest in wide-scale road rehabilitation projects in order to more effectively support other areas of development.

- Rehabilitate electrical power grids to provide widescale access and increase the number of hours/day that residents have electricity (including establishment of new transformers, rehabilitation of existing transformers, and providing generators)

- Advocate for increased fuel availability and affordability to improve transportation issues and power generators and heaters.

- Prioritize dissemination of heaters and heating oil for warmth in winter months

Water, Sanitation, and hygiene (wash)

A lack of essential household services, particularly water and sanitation, significantly hinders the safe return of Yazidis. Access to clean water is difficult throughout Sinjar, which negatively impacts consistent school attendance (especially for girls), the health and safety of environments children play in, and the overall ability of individuals to maintain their personal hygiene. Overall, women in Sinjar experience the shortage of clean water more significantly than their male counterparts.

Findings

65% of respondents do not have access to enough water, while over 70% of respondents do not have consistent access to clean water.

When individuals were asked to list all challenges relating to water access in their communities, roughly 54% of individuals cite a combination of low supply, long wait times, and sporadic availability as major challenges to water access in the community.

17% of survey respondents attribute their dissatisfaction with their water supply to a combination of low supply and bad taste or smell of water.

24% of women and 73% of men state that water for personal hygiene is affordable.

Recommendations

- Improve access to clean water through comprehensive water projects (addressing both access and quality standards) to meet the needs of the vast majority who cite this as a major concern.

- Prioritize population hubs for water access and water quality interventions.

- Improve planning of water distribution networks to ensure equitable access.

Healthcare

ISIS attacked the healthcare infrastructure in Sinjar by looting medical devices1 and destroying Sinjar General Hospital and smaller medical centers in the region.2 In 2020, 90% of villages and towns in Sinjar were suffering from a lack of healthcare services and there were only 3 qualified and functioning healthcare centers to serve an area of 72 villages.3

Survey data for this report found that healthcare in Sinjar is plagued by several constraints. Limited supplies, poor quality care, and troubled access hinder the healthcare sector across the entire region, and women are disproportionately impacted by limitations in accessing quality and specialized healthcare services.

Findings

45% of Yazidis across Sinjar have experienced being unable to access necessary medical care. In both north and south Sinjar, the primary reasons for the inability to access medical care are cost and lack of doctors.

67% of respondents are unable to purchase necessary medications.

82% of respondents highlight that the number of available medical professionals is insufficient.

95% of female respondents attribute their inability to receive medical attention to the lack of available doctors.

- Nearly 64% of respondents note that medical facilities do not have the necessary supplies and medications needed for the community.

- 77% of women and 58% of men experience lack of access to medical supplies.

- 51% of individuals who do have access to medical care do not believe that they receive good quality care. 77% of women do not feel they have access to good quality care compared to 26% of men.

Recommendations

- Support primary healthcare centers and general hospitals to improve the quality of their care to prevent the need for residents to travel long distances to access medical care. This includes providing advanced training for current healthcare staff.

- Mobilize international pressure on the Government of Iraq (GOI) to adequately staff all healthcare facilities in Sinjar.

- Increase healthcare support in rural areas given the distance to existing general hospitals. This may include building or rehabilitating primary healthcare centers as well as furnishing and equipping them.

- Provide medical equipment and supplies to existing general hospitals and primary healthcare centers.

- Prioritize women’s healthcare, including access to maternal and reproductive healthcare.

1 Ibid.

2 Aziz, Ammar. “Shingal (Sinjar) in Need of Doctors.” Kirkuknow, 30 Apr. 2022, https://www.kirkuknow.com/en/news/68014

3 ACAPS. (2020). Iraq: the return to Sinjar. Retrieved from: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20201120_acaps_briefing_note_sinjar_province_iraq.pdf

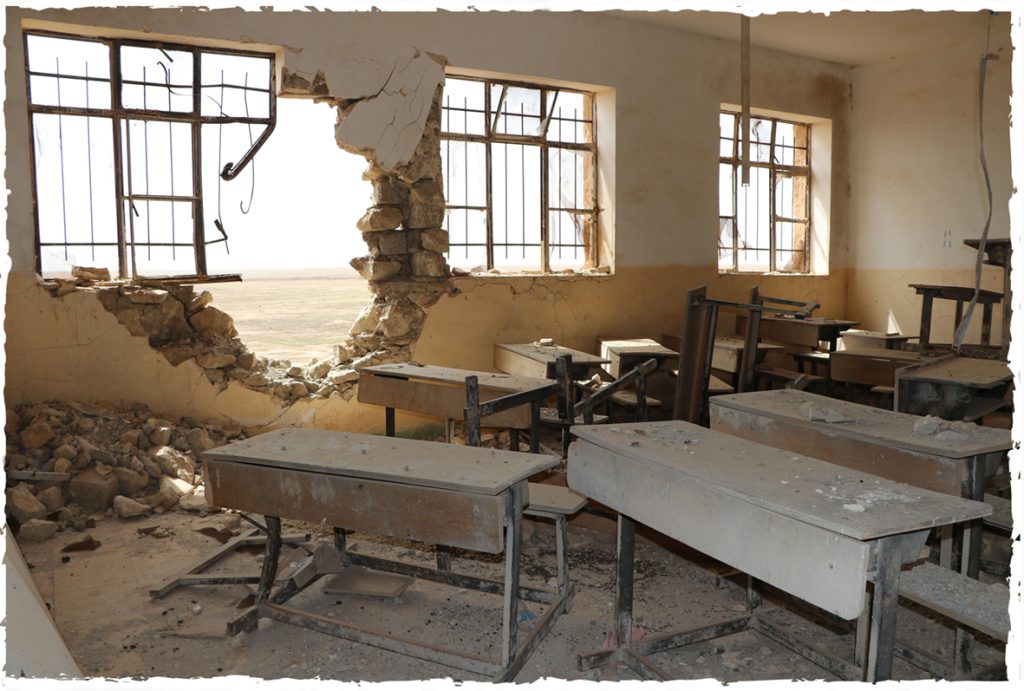

Education

The Iraqi education system has struggled for decades due to ongoing conflict and violence, and Sinjar’s education sector has historically been neglected by consecutive Iraqi administrations. However, the situation in Sinjar post-2014 is particularly devastating. ISIS militants used school buildings as military bases, which were then targeted in air strikes. Teachers were forced to flee, and vast numbers of children remained out of school for prolonged periods of time. Since the violence abated, some school infrastructure has been rebuilt, but many of Sinjar’s qualified teachers remain displaced and unable to resume their work.

Findings

60% of girls and 45% of boys have never been enrolled in school. Of those who do attend school, 48% of girls attend regularly compared to 57% of boys.

Respondents cite several factors that decrease the quality of the educational offerings in Sinjar, including lack of electricity, school supplies, and qualified teachers.

53% of respondents in south Sinjar report that children can get to school safely, compared to 70% of respondents in the north. Respondents cite a number of factors as major obstacles to safe school access, including the presence of armed forces and active landmines.

- Of those who do attend school, none attend a full 5 days per week. 65% in the south and 35% in the north are in school 3 days per week.The remaining children (35%

in the south and 65% in the north) attend school 1 to 2 days per week. - Of those who do attend school, 99% in the south and 86% in the north attend school 3 to 4 hours per day.

Recommendations

- Mobilize international pressure on GOI to adequately staff schools and train teachers in Sinjar.

- Increase access to schools, especially in rural areas, either through increased rebuilding efforts of local schools or transportation programs.

- Prioritize security mechanisms for school children to reduce threats of injury and the potential for interaction with armed actors on the way to school.

- Further investigate the enrollment rates of eligible children, given the historically low enrollment rates and the disparate enrollment rates for girls versus boys.

- Undertake an overall assessment of education quality (supplies, teacher trainings, facilities, etc.) to buttress ongoing aid efforts to expand access.

Livelihoods

Before the genocide, most Yazidis relied on wheat and barley agriculture, as well as the large cement factory outside of Sinjar City, for their livelihoods. The genocide left these sectors and most others entirely decimated – agricultural lands were contaminated, farming structures and small businesses destroyed, and the cement factory was demolished in the crossfire. As a result, families are experiencing devastatingly high unemployment rates, little access to income, and increasing poverty rates and food insecurity.

Findings

52% of this study’s respondents indicate that their pre-2014 livelihoods were destroyed during the genocide.

95% of Yazidi women indicate that they would benefit from a small business loan. This number increases to 97% in female-headed households.

62% of respondents note that not a single member of their family has consistent income each month, even if they are able to secure some support from governmental assistance or non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

- 65% of those living in north Sinjar and 26% of those in south Sinjar have been able to rebuild their livelihoods, but they remain unable to generate consistent income that is adequate for their household needs.

- Over 50% of respondents note that their household incomes are generally insufficient to meet their basic needs.

- Only 20% of respondents can claim that at least 1 household member has a job.

- 59% of male respondents feel that their income is mostly sufficient for their basic needs, whereas only 41% of women feel the same.

- 40% of all respondents consistently have enough food, 45% sometimes do, 12% rarely do, and 3% never do.

- 30% of all respondents have consistent access to healthy food, 40% sometimes do, 25% rarely do, and 5% never do.

- Nearly 88% of survey respondents note that no one in their household participates in a cash-for-work program despite half of the population being unable to meet basic needs.

Recommendations

- Expand livelihoods programming to reach a wider section of the population.

- Pay specific attention to the livelihoods needs of women, especially women in female-headed households, in order to increase economic development and support social equity.

- Invest in women’s livelihoods by supporting the creation of small business and rehabilitation of farmlands.

- Support the provision of quality food across Sinjar by investing in rehabilitating farmlands.

Protection

For Sinjar residents, safety and security remain elusive, despite the region’s liberation from ISIS. Multiple political and armed groups continue to vie for influence and control, while airstrikes and international hostilities threaten the region’s safety and stability. Finally, during the ISIS occupation, land mines were buried throughout the region, buildings were booby-trapped, and unexploded munitions were left behind as the group fled. These remnants remain scattered throughout Sinjar.

Findings

Approximately 70% of respondents – 80% in the north compared to 59% in the south – report that airstrikes are a primary safety concern in their community.

Approximately 55% of respondents – 87% in the south compared to 23% in the north¬ – report that landmines are a threat in their community.

Approximately 53% of respondents – 85% in the south compared to 21% in the north – report that leftover munitions are a threat in their community.

Approximately 49% of respondents – 56% in the north and 45% in the south – report that armed groups are present in their community. 84% of all women, equally in the north and south, acknowledge that militarization is their current primary fear.

Recommendations

- Mobilize international pressure to create, implement, and enforce agreements aimed at ensuring regional stability and security.

- Ensure meaningful Yazidi representation in diplomatic efforts to resolve regional disputes.

- Support a community-nominated candidate for mayor of Sinjar.

- Mobilize international pressure to de-mine all areas of Sinjar, focusing particularly in the south where fewer interventions have been made.

- Provide support for Yazidis to acquire proper documentation for such things as land ownership or government services.

Gender-based violence (gbv)

ISIS’ targeted attacks on Yazidi women amount to one of the most atrocious examples of gender-based violence in current history. While mass atrocities, genocides, and war all have devasting effects on the mental health of survivors, sexual violence survivors often struggle for decades to reclaim their psychological well-being and sense of safety. As a result, the need for psychosocial support for women returnees to Sinjar is immense and sorely lacking.

By targeting Yazidi women, ISIS impacted the norms of family composition in the region, as well as the well-being of future generations of Yazidis. In the majority of single-headed households, a woman is now primarily responsible for all aspects of the home. This increased burden of survival has profound impacts on her psychosocial well-being and that of her children who are also in dire need of psychosocial support. The long-term ramifications to future generations include the prevalence of child marriages across Sinjar.

Findings

98% of women note that community building activities and women’s spaces, like the ones they experienced as part of data collection for this study, have an immensely positive impact.

29% of women report no access to psychological services and 25% report limited access. The needs are greatest in highly populated areas, where over 40% of women have zero access to services compared to 21% in semi-populated areas and 32% in rural communities.

Almost all surveyed women acknowledge that women in the community would benefit from psychological support and would take advantage of it if it were more readily available

93% of respondents in this study note that children in rural and semi-populated areas would benefit from access to psychological support, though services are nearly non-existent.

- 63% of women state that there is access to psychological support in the community and many mention short-term psychological interventions that they benefitted from in the past but wished had had a longer duration.

- 36% of women indicate that seeking psychological support, even if it were more readily available, brings with it a sense of embarrassment.

- 40% of women note that it has not been easy to re-integrate into the community and 14% are not sure that they belong in the community anymore.

- 88% of residents in rural communities, 96% in semi-populated communities, and 100% in highly populated communities report the presence of child marriage.

Recommendations

- Invest in long-term psychosocial support and community healing processes, which include women and children.

- Support the development of women’s spaces and centers that allow women to access the benefits of community and belonging without the embarrassment associated with seeking psychosocial support.

- Support and enhance cultural and religious activities, as part of the healing process.

- Support women’s economic empowerment in order to bolster psychological well-being.

- Acknowledge the connection between women’s access to livelihoods and their psychological well-being by investing in livelihoods programs specifically for women.

- Empower women to self-direct their own healing process.

- Expand psychosocial interventions to address the high rates of child marriage.

- Expand access to psychosocial care for children, especially former captives of ISIS.

Case Studies

Despite the challenges, 150,000 Yazidis have returned to Sinjar with the hope that the region will recover.

55-Year-Old Female, South Sinjar

I am from Kocho in south Sinjar. When it was captured by ISIS, we came here to Tel Qasab. My husband – who was so youthful – and 2 of my sons were killed.

Read more...36-Year-Old Female, North Sinjar

Health services in Sinjar are generally very poor, and I think obstetrical delivery is the most critical healthcare challenge facing us here.

Read more...49-Year-Old Male, North Sinjar

I have 6 children. My youngest son was born in 2006 and my eldest son was born in 2004.

Read more...26-Year-Old Female, North Sinjar

Multiple organizations work here among us, including Nadia’s Initiative, which is one of the organizations working the hardest.

Read more...43-Year-Old Female, South Sinjar

I do not feel safe and secure here. In fact, no one feels secure in Iraq – we can never rest assured in this country, because there are always wars.

Read more...

“Help us build a better, safer, and more just world for future generations.” – Nadia Murad

For more information, please visit www.nadiasinitiative.org

Acknowledgements

This report was supported and developed by NI in collaboration with the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security (GIWPS). The report was primarily authored by Amber Webb and Nora El Zokm (DARNA Research ApS), the lead researchers, with analytical support from Marlana Salmon-Letelier and Garrett Tusler. Data collection on the ground in Sinjar was supported by NI’s protection team. Several aid organizations in Iraq also contributed by offering their networks of contacts and previous research for review. Most importantly, this report would not be possible without the participation of hundreds of Yazidi families in Sinjar who generously offered their time and feedback.

Photography

Courtesy of Nadia’s Initiative. Images should not be reproduced without authorization. To protect the identities of those who participated in the research, all names have been withheld.